Calgary, Alberta, Canada | Type: Ideas Forum | Size: N/A | Year: 2017

Total City –

Due, in part, to global urbanization, the mass exodus from rural into urban centers has brought dwelling back into current architectural discourse and raised pressing questions such as, who’s responsibility is it to determine how to best manage the shear scale of this demand for housing? Does this responsibility reside with the public sector (ie. Municipal Governments, Urban Planners, Architects, etc.) or the private sector (ie. Speculative Developers, Banks, Pension Funds, etc.)? and lastly, How will the scale of this development change or alter the larger grain of the city?

“Where housing once used to be a typology in which architects could intertwine the most progressive of their approaches towards space, technology, living and politics,”[1] today, through contemporary society’s predilection towards the smooth and frictionless space of capitalism, where we live has “become a tool of capital complicit in a purpose antithetical to it’s social purpose.”[2]

This paradigmatic shift has fundamentally changed the architect’s role from that of social agent to economist as the leitmotif of design appears to reside less within the realm of innovation and experimentation, but rather adheres to the gentrifying forces of proformas, real estate specifications, zoning restrictions, architectural controls, etc. This current paradigm from which we continue to both theorize and ultimately construct housing appears to lack a cohesive, recognizable, ideological agenda outside of maximizing profit. This has dire consequences with respect to the agency and future of our profession.

TOTAL CITY began as a conversation, first around the worktable at our office, then within the architectural studios we teach at the University of Calgary, where we questioned: a) when did the initiative to both theorize and ultimately construct housing shift from the responsibility of architects to the domain of the private sector (ie. speculative development)? and b) whether or not history could provide evidence of a time when this situation was reversed and architects were an agent of change and progress, with housing at the center of that ideal?

Our research uncovered a brief moment in the early days of Modernism where architects such as Hans Meyer, Gerrit Rietveld, Bruno Taut, etc. used housing as a vehicle to explore some of their most radical theories pertaining to dwelling and the city, as such privileging housing as one of the fundamental typologies of early modernism.

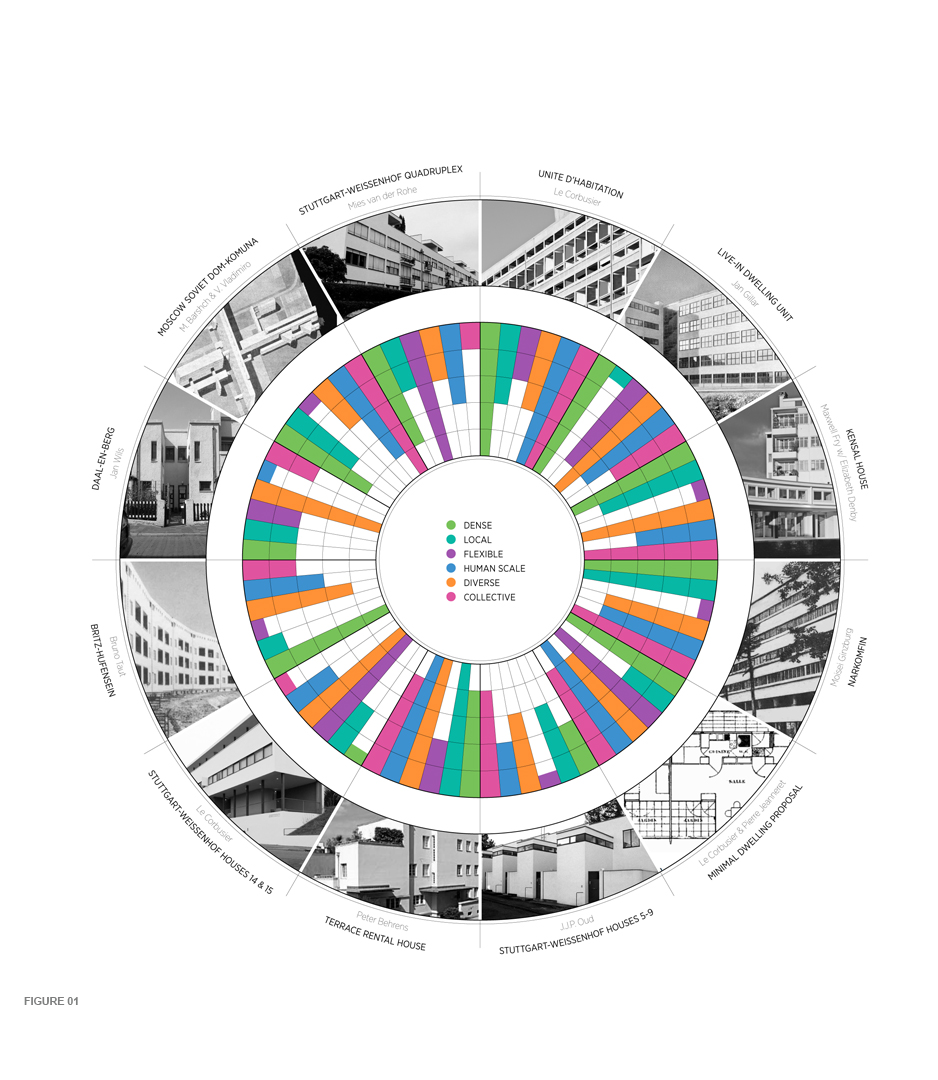

Figure 01 graphically captures some of this research via curating a selection of early modernist projects that demonstrate a predilection towards innovate solutions for housing that express a kind of cultural will about how the city should be designed.

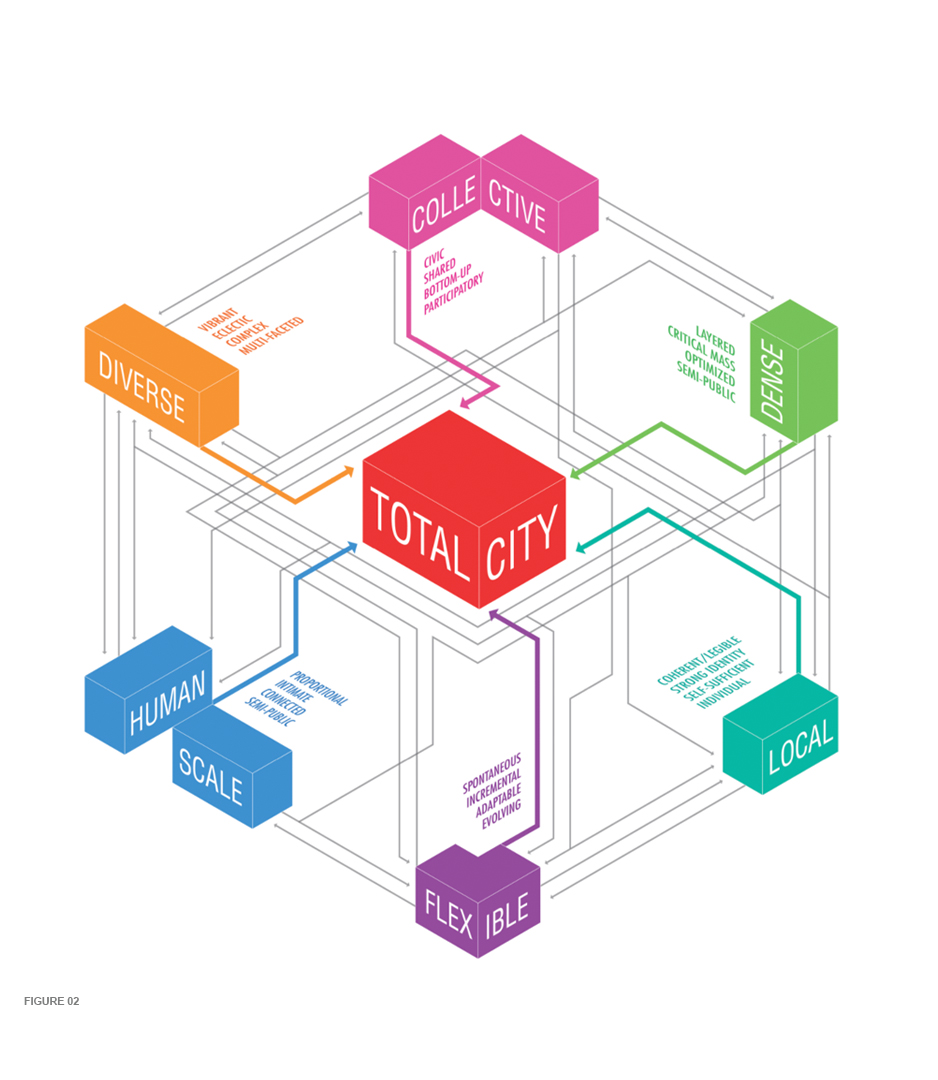

As can be seen in Figure 02, six themes or formal drivers were distilled from this body of research; flexibility, diversity, collective, human-scale, local and density. Historically, each theme endeavoured to enhance quality of life through formal and programmatic solutions that embraced a multiplicity of uses and the complexities of how people lived.

As a caveat of sorts, while some might argue that these six themes of flexibility, diversity, collectivity, human-scale, local and density continue to be referenced within the field of housing today, we would argue that private development has gentrified these themes into slick marketing campaigns that promote a ‘generic desirability’ in an effort to leverage the ever-widening gap between quality, value and profit.

As such, TOTAL CITY wishes to expose the gentrification of these themes by private development – both at the scale of multi-residential housing and by extension the city – through critical inquiry into a selection of global housing initiatives (both built and conceptual) that contest the banality and ubiquity of present-day housing stock through their creative reanimation of the six themes… Stay tuned!

[1] Maltzan, Michael. “Identity, Density and Community in the Un-Model City.” Harvard GSD, 2011